With his lavish hotel atop

Steptoe Butte, celebrity homesteader Cashup Davis elevated the Palouse

experience

Story

by Jeff Burnside, special to Pacific NW Magazine of the Seattle Times 8/5/2022

CUTLINE: At the grand opening of Cashup Davis’ hotel, on July

4, 1888, guests lined the ground-level porch and the roof’s viewing platform.

From Steptoe Butte, one of the highest points in the Palouse, guests were

treated to vistas of rolling hills and farmland, plus a rare look inside a

telescope that was considered one of the most powerful in the state at that

time. (Courtesy Whitman County Historical Society, Perkins House,

Colfax) #

Editor’s Note: The following is an

edited excerpt from “Cashup Davis: The Inspiring Life of a Secret Mentor,” by

Jeff Burnside and Gordon W. Davis (Basalt Books, Aug. 15, 2022, $18.95

paperback; available at basaltbooks.wsu.edu and at Pacific

Northwest booksellers; see cashupdavis.com).

“The mountain became a motto to the

man.”

— New York Evening Post article about Cashup Davis

CASHUP DAVIS STOOD on the 14-by-14-foot cupola atop his new

hotel, perched on one of the highest points in all of the Palouse — Steptoe

Butte, which he now owned — and looked out over every homestead and every town

from horizon to horizon: “a land of peace and plenty.”

Davis’ lavish hotel was

ready to open with great fanfare on July 4, 1888, honoring the birthday of his

adopted nation.

At that very moment, he had a lifetime on which to reflect.

The confident, short, charismatic British kid who came to the United States

with an obsession for the American West now was standing over a region that was

the very definition of the western edge of settlement. He had beaten the odds.

He had proved his doubters wrong. He had stuck to his vision. His heart was

full. Davis would be forgiven for feeling like a king.

CUTLINE: The story of

Washington homesteader and celebrated hotel owner James S. “Cashup” Davis is

examined in “Cashup Davis: The Inspiring Life of a Secret Mentor,” by Jeff

Burnside and Gordon W. Davis. (Courtesy Basalt Books)#

Indeed, the castles that surrounded him during his childhood

in southern England plausibly did inspire him to build his own castle, in

sparking his vision, in imagining this hotel.

Residents all around the Palouse and newspapers across the

nation were talking about his hotel. “balloon ascension and fireworks will be

features of the occasion, while the evening will be devoted to dancing,”

reported The Lewiston Teller and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “Within a

short time, Steptoe will be the most attractive place for a visitor in the

whole inland country,” reported the Spokane Falls Review.

CUTLINE: This 1888 news clipping from

The Lewiston Teller reprints a story from the Colfax Gazette touting the

upcoming grand opening of Cashup Davis’ new hotel on Steptoe Butte. For the

event, Davis arranged for a balloon ascension, fireworks, music and dancing.

Admission was 25 cents and included a peep through Davis’ vaunted telescope,

“the second largest” in the Washington Territory. (newspapers.com) #

Davis, so determined, spent much of his fortune on it.

Pioneers must have looked on in envy that someone could complete such a project.

As one newspaper put it, “He was known as the money king of the Palouse

country.”

DAVIS’ GUESTS began arriving.

The first sight they encountered upon entering the front

doors was a large, ornate ballroom 60 feet long and 44 feet wide, dominating

the main floor, with a kitchen, and a stage that held performances of all kinds

to dazzle his guests: orchestras; singing; a recital; Chautauqua features;

“Punch and Judy” shows of the era; and a “magic lantern” box with viewfinders

using smoke, mirrors and focused sources of light (two years before electricity

came to nearby Farmington).

CUTLINES

1 of 2: The hotel’s grand ballroom featured an exhibit that displayed and

celebrated the crops of the Palouse. In this photograph, taken around 1890,

Reverend Todd and Reverend Sproat relax in the... (Courtesy the collection of

Jim Martin, restored)#

2 of 2: The hotel’s grand ballroom featured an alcove near the front entrance

that displayed and celebrated the crops of the Palouse. (From the collection of

Jim Martin, restored)+

In an alcove near the entrance, they saw Davis’ display of

the crops of the Palouse: “beautifully decorated with all the grains, fruits

and cereals that are available in this country.” He was a one-man Chamber of

Commerce. On the walls in this display room were

framed sketches of world-famous people, bridges, boulevards, steamships and

cities, including a scene of New York Harbor near Pier 15, where Davis had

arrived from England.

It all seemed to applaud grandeur and the immense possibility

of industry. And that the Palouse was right up there with the big boys. It was

so Cashup.

GUESTS RINGED THE ballroom from a balcony, looking down at

the dancing and hubbub below. The second floor also had a dining room for 50

people. From that balcony, guests accessed their rooms, “fitted up in

comfortable style and every convenience and attraction … to make time pass in

this great Northwestern pleasure resort like a happy dream,” the Spokane Falls

Review wrote.

As the guests filed throughout the hotel, they saw

hand-carved wood trim — an elegance that evoked the finest quarters of Paris or

New York. Davis’ hotel was not by any means as ornate as the world’s great

hotels. But it made these tough pioneers feel pretty special.

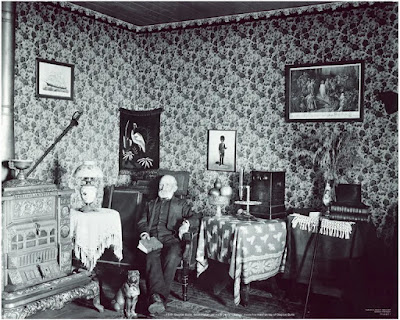

CUTLINE: Cashup Davis invited his more important guests to his private lounge —

his “VIP Room.” The lounge contained scientific instruments, his famous

telescope and other prized possessions. In the lower left of this photo, taken

in 1888, is an ornate “modern” heating stove. (Courtesy Jim Martin)#

The most important guests were invited into a lounge that

served as Davis’ private quarters — a VIP room, of sorts, where he could hold

conversations. It was a showcase of his life. A photograph

of Davis in this room shows him sporting his trimmed white beard,

sitting upright in an armchair wearing a full suit, vest, white shirt and tie.

His fingers are holding his place in the open book resting on his knee.

On the walls, he had hung sketches important to him. His

lounge also included a rare microscope, a stereoscope photo viewer, an

elaborate heating stove (a new product in America) and Davis’ prized

possessions: his top hat, his telescope and the sword he carried by hand when

immigrating to the United States from England in 1841.

THIS DAY, JULY 4, 1888, Davis worked the crowd, “beguiling

his visitors,” to make them feel welcome, as he had

done so successfully at his famous stagecoach stop just down the road. “In all that time of stress,” wrote S.C. Roberts, who was close to Davis

and his family and who wrote pioneer essays for local newspapers, “he met every

guest as though he were a notable dignitary, and entertained him

royally.”

CUTLINES

1 of 2: One of the

best surviving portraits of Cashup Davis was taken by a studio photographer in

Oakesdale, near Steptoe Butte, around 1888. (Courtesy Davis Family Collection)#

2 of 2: Another

surviving portraits of Cashup Davis, taken about 1882. (Courtesy Davis Family

Collection)#

Davis brought in a 10-piece horn section with a

percussionist, likely led by Cy and Andy Privett of Colfax, who had been so

popular at his stage stop. The guests celebrated under those fireworks and that

hot-air balloon ascension and kept dancing until dawn.

His first day was a smashing success. And it made for a future

of near-certain popularity. To help ensure that, Davis wisely coordinated an

1888 horse-and-buggy version of a shuttle van for his guests to get up to the

summit and navigate the sometimes-harrowing, winding road carved into the steep

slope. It wrapped around the butte several times and switched back and forth as

it snaked upward to the summit, where guests were dropped off at the front door

like royalty.

CUTLINE: An artist’s rendering of Cashup Davis’ lavish hotel on Steptoe Butte

shows just how grand it was at a time when only a few thousand settlers lived

in the region, many in rudimentary housing. It opened in 1888, closed in about

1904 and burned down in 1911. (Illustration by Noah Kroese)#

As only he could do, Davis, a celebrity in his own right,

hired a celebrity stage driver to run the shuttle. His name was Miles Kelly

Hill. Everyone knew him by his nickname: Shorty. He had driven stage for the

legendary Felix Warren and had stopped many times at Davis’ stage stop. Shorty

had a reputation as the best bronco rider and stagecoach driver around. And he

was, like Davis, entertaining, on the short side and full of

charisma.

“It’s pretty darn steep at the top and pretty narrow,” says

Dave Wahl, a cowboy poet in his 80s living in Genesee, Idaho, who, as a young

boy, grew up listening to Shorty’s extraordinary stories, including about

Davis’ hotel. “In those days, it was all gravel, and it was more narrow and

steeper and more windy,” says Wahl. He described Shorty thus: “He was bowlegged

as a wish bone you could walk a pony through.”

CUTLINES

1 of 2: This is the only known photo of the entire James S. “Cashup”

Davis family, taken in Wisconsin in 1860. Cashup and wife Mary Ann are in the

back row, fourth and fifth from the left. Mary Ann holds their child Amy in her

lap. Amy became the family storyteller into the 1960s. (Davis Family

Collection, restored by Jim Martin)#

2 of 2: This is the only known

photograph of Cashup and his wife, Mary Ann, on Steptoe Butte. Reportedly, Mary

Ann did not like living on Steptoe and spent most of her time at the family

farm near the base of the butte. (Courtesy Davis Family Collection)#

PHOTOGRAPHY WAS STILL uncommon in 1880s Palouse,

but Davis gathered 114 guests, family members and friends to pose for a

photo outside the hotel one day early on.

There are conflicting dates attributed to the photo.

Scribbled in white on the photograph, as was normal back then, it says inside a

hand-drawn scroll: “STEPTOE BUTTE 3800 FEET HIGH. THE BEST PLACE IN WASHINGTON

TO GET A GOOD VIEW OF THE COUNTRY.” Then to the right, the same scribbler

wrote, “WE ARE WAITING FOR THE CAR.” To the far left is a surrey without a

horse. Perhaps it was Shorty’s, waiting to take guests back down the butte that

day.

In the foreground, a ladder and stone rubble affirm the

photo might indeed have been taken on the day of the grand opening. The people

stand shoulder to shoulder in front of the hotel, and still more are lining the

cupola on the third floor. There is a 10-piece horn band with a drummer. People

are wearing their finest clothes: men in dark suits with white shirts and dark

bowler hats, women in long full dresses tightly fitted around the torso, their

heads festooned with big flailing hats.

Sitting in front is Davis, flagged in a sea of dark suits by

his cloud-white hair and beard.

CUTLINE: An 1866

tintype portrait of James S. “Cashup” Davis. (Courtesy John Rupp and Linda

Banken)#

THE MAIN ATTRACTION of the hotel was Davis. But the

second bill was perched at the top inside that observatory and reading room:

the large brass telescope. In 1888, people had never seen anything like it. The

Lewiston Teller and Seattle Post-Intelligencer pronounced: “A peep through the

big telescope is worth the 25 cents charge for admission.”

Just after the grand opening, an authoritative book

reported about the telescope. “With

its aid, a view, scarcely to be paralleled in the country, is spread out like a

map. A foreground of vast rolling plains checkered with grain fields; a

background of towering mountains, rising, tier on tier, till they break at last

against the barriers of eternal frost — such is the outlook which daily greets

the vision of this brave old pioneer of the Palouse.” “Cashup’s Pride,”

it was called by some.

“When Mr. Davis purchased this historical hill, many of his

friends thought he was out of his head, but those who have visited the place

have changed their minds wonderfully,” gushed the Spokane Falls Review. “Cash

Up cannot be other than voted an enterprising and progressive man. His

advertising the butte as he is not only benefits himself, but the entire

country and community.”

CUTLINES:

1 of 2: In 1879, James S. “Cashup” Davis had plans drawn up

to expand his Whitman County home into a store and dance hall that quickly became

one of the Northwest’s most famous stagecoach stops. (Courtesy Jim Martin)#

2 of 2: James S. “Cashup” Davis

expanded his home into a thriving store and stagecoach stop. This is where he

earned his nickname “Cashup” and became one of Washington’s early celebrity

pioneers. (Courtesy Jim Martin)#

DAVIS KNEW HE had a good thing going. And he sought to

invest in his hotel and his Steptoe Butte operations with improvements and

events. In about 1890, he added a covered porch around the entire hotel that

was 10 feet deep, creating more floor space for large crowds and allowing

people to relax outside while taking in that view.

He planned a convention at the hotel to bring together

Native American leaders and American historians to clarify that, contrary to

popular belief at the time, the Battle of Pine Creek had not taken place on

Steptoe Butte. He knew he no longer could claim that his hotel was the site of

this battle, but it surely could be the site of that discussion.

In May 1891, Davis hosted a “temperance ball”

at the hotel, celebrating the era’s push against alcohol. The period was called

“the second wave of temperance.” Alcohol was a problem in many areas of the

United States, including the pioneer west, where saloons were plentiful.

Fundamentalist religion was quite prevalent on the Palouse, and local churches

worked toward temperance.

Davis’ hotel, and his stage stop before that, was known for

parties and good times, so he was eager to demonstrate to the community

that they could have fun without alcohol.

CUTLINES

1 of 2: Mary Ann Shoemaker Davis, the

wife of James S. “Cashup” Davis, circa 1885. (Courtesy John Rupp and Linda

Banken)#

2 of 2: A sketch portrait of Mary Ann Shoemaker Davis, the

wife of James S. “Cashup” Davis. (Courtesy Linda Bakken, John Rupp and Heather

Forseth)#

DAVIS’ APPLE TREES, planted along the slopes of the butte,

were mature and in full production now. As a result of his wise varietal

planting, he provided his hotel guests with fresh apples many months of the

harvest season. The apple trees, while now partly covered in overgrowth, still

produce delicious and rare varieties of apples, left to the deer and other

wildlife.

The success of the hotel paralleled the expansion and

productivity of the Palouse. Electricity lines gradually were built.

Cars were still more than a decade away, but new railroad lines continued to

slice the region and, with them, boost commerce and bring more people to the

area. The Territory of Washington became the State of Washington just 17 months

after the hotel opened.

One newspaper account said Davis was

considering building a monument to pioneers at the top. And he told people that

he wanted to be buried at the summit; he even had a shovel with which he

himself someday would dig his own grave.

CUTLINES:

1 of 2: An elaborate horse- drawn hearse carrying the body of James S. “Cashup”

Davis leads his funeral procession in 1896 to the Bethel Cemetery, where his

large tombstone stands to this day in the shadow of Steptoe Butte. (Washington

State Archives)#

2 of 2: The

Spokesman-Review published the most succinct headline of Cashup Davis’ death on

June 24, 1896. Davis returned early from a morning squirrel hunt with a hired

man, and seemed out of breath. He lay down to rest and died shortly after.

(newspapers.com)

Davis had achieved such prominence that, according to the

Garfield Enterprise, there “has been considerable discussion on the various

local papers concerning the name of a noted landmark”

renaming Steptoe Butte to “Cashup’s Butte” or something similar.

BUT, AS ALMOST anyone who achieves great success can attest,

Davis had detractors. And things got a little ugly. The ugliest might have come

from The Spangle Record, which wrote a scathing, personal

attack on Davis, saying, “Mr. Davis was high cockalorum in the Palouse

country,” an old phrase that means a little man who incorrectly has a very high

opinion of himself; low-level and unimportant.

Ouch. It got worse. The newspaper writer accused Davis of

taking advantage of farmers desperate for cash, claiming he famously offered to

pay in cash but then would use that offer to get a low price, then haggle the

price further downward, make the deal — but pay half in cash and half “in a few

days, when the Portland mail comes.” Without attribution, the article reported,

“One settler says men have grown old and died of old age waiting for the

‘balance’ on the ‘Cash-Up’ trade.”

Given Davis’ abundant self-confidence — and some arrogance —

he likely drew energy from his detractors and pushed even harder.

A New York newspaper reporter put it this

way: “I think in some way, ‘Cashup’ and Steptoe drew little by little nearer together, because

they are so similar. Both are sturdy, upright, downright individuals,

maintaining the dignity of higher plateaus amid the lower range by which they

are surrounded. The subtle air or the swift wind could not affect the integrity

of either. I think somehow the mountain became a motto to the man, and he

demanded from and gave to his neighbors its sheer and undeviating honesty.”

The Spokane Falls Review wrote of Davis and his successful

hotel, “There he has built an imperishable monument to himself in the form of

his observatory and other buildings [overlooking] the fertile land at the foot

of his castle.”

What made the hotel so special was that it perched on top of

one of the greatest heights on the Palouse. Yet that great height also would be

its greatest downfall, as Cashup Davis was about to learn.

Jeff Burnside is an

investigative reporter born and raised in the Seattle area. He's the recipient

of numerous journalism awards including 10 regional TV news Emmys, former

president of the Society of Environmental Journalists and a judge for both the

Meeman and Oakes journalism awards. Reach him

at jeffburnside@outlook.com or jeffburnside.com

Also see ‘In the hills of

the Palouse, and in his life, pioneer Cashup Davis aimed high, no matter the

risks’

https://pullman-cupofpalouse.blogspot.com/2022/08/in-hills-of-palouse-and-in-his-life.html

.jpg)

.JPG)